Tourists flock to Bran Castle, known locally as “Dracula’s castle,” though it has little to do with the 15th-century prince Vlad Tepes, who inspired the wildly popular vampire story. A billboard announcing the park site went up near the town of Sighisoara. The town of Sighisoara, where Prince Tepes was born in a house that is now a restaurant-just a taste, say critics, of what lies in store for Transylvania. Matei Dan, Romania’s minister of tourism, decided in 2001 that it was “time Dracula went to work for Romania.” The house of “Vlad the Impaler” lies in the center of Sighisoara’s well-preserved, walled historic district, which dates to the 13th century and has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Uproar from preservationists, including England’s Prince Charles, prompted planners to find another site for the Dracula Park. Dracula Park is now slated for Snagov, a sleepy village near the Bucharest airport, and could open as early as the fall of 2004. This Snagov churchyard will likely be spared.

The Breite Plateau, a broad sheep-grazing ground of 300 acres or so, lies a couple of hundred miles north of Romania’s capital, Bucharest, but only a ten-minute car ride from Sighisoara, the city of 38,000 that owns the land. Interspersed here and there across the plateau are 120 venerable oak trees. When I drove from Sighisoara to Breite to see those gnarly giants not long ago, I was accompanied by a couple of earnest young environmentalists who darkly warned that the trees would soon be felled. A large white billboard explained why. “Aici se va construi DRACULA PARK,” announced the text in crimson letters: something called Dracula Park was to be built there. Over the past year and a half, a furious controversy surrounding this proposal has focused attention on an area so obscure that many people today still assume it’s fictitious: Transylvania. But located high within the curling grip of the rugged Carpathian Mountains in central Romania, Transylvania is as real as real can be-rich in mineral resources, blessed with fertile soil and filled with picturesque scenery. Although its name means “land beyond the forest,” this historical province of more than seven million souls was not known as a particularly spooky place until 1897, when the Irish writer and critic Bram Stoker published his sensational gothic novel Dracula. Casting about for a suitable backdrop for his eerie yarn about a nobleman who happened to be a bloodsucking vampire, Stoker hit upon Transylvania, which he described as “one of the wildest and least known portions of Europe.”

As it happened, Stoker never set foot there himself. English libraries provided all the maps and reference books he needed. His ghoulish imagination did the rest. Count Dracula, he of the “hard-looking mouth, with very red lips and sharp-looking teeth, as white as ivory,” inhabited “a vast ruined castle, from whose tall black windows came no ray of light, and whose broken battlements showed a jagged line against the moonlit sky.” Dracula proved to be one of those rare tales that tap a vein deep within the human psyche. The book has never been out of print, and Transylvania, through no fault of its own, is doomed to be forever associated with the sanguinary count. Which explains both the billboard that went up last year on the Breite Plateau and the outrage it provoked. It was Romania’s own minister of tourism who came up with the idea of building a Dracula theme park in the heart of Transylvania. For the region as a whole, and in particular for the city of Sighisoara, it’s only the latest chapter in a long history of unwelcome intrusions from the outside.

It began with the Romans, who arrived late in the firstcentury to impose their harsh discipline and Latin tongue on the ancient Dacian people native to the area. Next came the Magyars from what is now Hungary, followed by various barbarians and Mongols, then the Turks of the Ottoman Empire. Back and forth they all went in true Balkan style, and the dust never quite settled. Romania did not even exist as a nation before 1859, when, in the wake of the Crimean War, the principalities of Moldovia and Walachia united as a single state. Transylvania belonged to Austro-Hungary until 1918, when the Allied powers awarded it to the Bucharest regime after World War I. No matter what flag flew over it, though, Transylvania has been divided for centuries roughly between three ethnic groups: Romanians, Hungarians and Germans. The Germans left the most indelible mark. Colonists from the Cologne archdiocese-Saxons, they were called, because in those days Germany didn’t exist, either-first came to Transylvania during the 12th century. They preferred hills for their villages, walling them and grouping their houses in tight, defensible rows. Strategically placed in the centers of those citadels were the churches, the last sanctuaries into which an embattled population could retreat. The Saxons made sure their houses of God were as much fortresses as places of worship: massive stone towers with battlements and sentry walkways surrounded by walls with reinforced gates and defensive trenches. Some 150 of these mighty fortress churches remain in Transylvania today, and they are rightly valued among Romania’s greatest national treasures.

The Saxons were talented, thrifty and hard working, but they also tended to be clannish, maintaining their own sectarian ways through the centuries. German schools invariably stood near German churches, and even today, 800 years after arriving in Transylvania, some Saxons still speak German, not Romanian, which antagonizes non-Saxons. Nicolae Ceausescu, the late, unlamented dictator who imposed a weirdly personalized form of communism on Romania from 1965 to 1989, was a fervent nationalist who actively strove to get rid of the minority Saxon culture.

In the end it was the minorities who finally got rid of Ceausescu. It happened more than a dozen years ago, and the place where trouble started was the city of Timisoara. After Ceausescu’s secret police, the Securitate, fired on crowds demonstrating there against the regime, a nationwide revolution flared up; within days, Ceausescu and his wife were condemned by an anonymous court and executed by a firing squad. When I arrived in Timisoara to cover that story, town authorities were still burying young people shot in the demonstrations, and the windows of my hotel room were pocked with bullet holes.

Returning to Transylvania last year, I found the area again in turmoil-this time over the plan to build Dracula Park. The chief promoter of that provocative scheme, Romania’s minister of tourism, Matei Dan, 53, had a sudden inspiration two years ago while visiting a Madrid theme park devoted to Spanish history: Why not a theme park devoted to Dracula?

When I interviewed Dan in his opulent Bucharest office, he was in shirt sleeves and seething with energy. He bounced around shouting, “OK, I knew my project was unconventional. Original! Shocking! But I want to use it to attract a million tourists a year. Elsewhere in the world there is a very big industry about Dracula worth hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars, but here in Romania it doesn’t exist. And so I decided it is time Dracula went to work for Romania.”

Few of his countrymen would argue with Dan’s economic rationale, but proposing Sighisoara as the project site was another matter altogether. Known as the “Pearl of Transylvania,” Sighisoara is the supreme example of a Saxon city. Founded as Schässburg toward the end of the 13th century, the old town remains perfectly preserved. It sits on a hill behind a 30-foot wall punctuated by nine defensive towers, each built by a different guild: the shoemakers, the butchers, the rope makers, and so on. Dan saw Sighisoara as a potential gold mine, with its cobbled lanes, beautiful buildings and stately towers. Not the least of its attractions is a hallowed house on the citadel’s main square, identified as the birthplace of Vlad Tepes-literally, Vlad the Impaler. Ruler of Walachia in the mid-1400s, Vlad became one of Romania’s most revered heroes for standing up to the invading Turks. His standard procedure for dealing with captives was to impale them on stakes, stick the stakes into the ground, then leave the unfortunates to die slowly. Legend holds that he once skewered no fewer than 20,000 victims in a single day. Vlad must have been familiar with the ancient belief that souls of the deceased who had been damned for certain sins could rise from their graves and wander the countryside between dusk and dawn, slipping into houses and sucking the blood of sleeping innocents. Romanian peasants guarded against this by driving stakes into graves to pin corpses down. Vlad’s father, who was governor of Transylvania before him, lived in Sighisoara from 1431 to 1435, and was known as Vlad Dracul. In Romanian, dracul means devil. That in a nutshell is the genesis of Stoker’s gruesome tale: the name, the place, the blood lust and the all-important wooden stake, which Stoker reduced in size and turned into a heart-piercing vampire killer. Vlad Tepes lived in Sighisoara the first four years of his life. This is why Dan made up his mind that the Dracula amusement park must go there.

In the autumn of 2001, the minister displayed his elaborate plans to potential investors in a glossy 32-page brochure. It depicts a medieval castle complete with torture chamber, alchemy laboratory, vampire den and an initiation hall where “young vampires can be dubbed knights.” The International Institute of Vampirology was to be located near Dracula Lake, a wide pond with a restaurant in the middle, and the Old Tower would house a workshop for teeth-sharpening. Restaurant fare was to include dishes of blood pudding, brains, and “fright-jellied” meat, a scraps and gelatin concoction.

When Dan’s plans were made public in November, many of Romania’s intellectuals and artists were horrified. The country had already suffered terrible depredations from Ceausescu’s frenzied construction projects. Now, critics said, the Dracula scheme would cause even more injury. Unfortunately for the park’s opponents, Sighisoara’s mayor, Dorin Danesan, turned out to be an enthusiastic supporter. Adapper, 44-year-old engineer, the outspoken Danesan was convinced that Dracula would bring thousands of jobs to town. He soon persuaded his city council to cede 250 acres of land on the Breite Plateau, right in the middle of those magnificent oaks, in return for a percentage of the park’s profits. “We’ve already had 3,000 pplications to work in the park,” he told me. “Everyone wants to profit from Dracula.”

Maybe not everyone. A travel agent from a nearby town said many people feel that Dracula creates a “bad image” for Romania. Dorothy Tarrant, an American scholar who has worked in Sighisoara for years, said she feared that the park would become a magnet for cultists. “They’ve had a medieval by young people with Satanic motifs, who are drinking and smoking pot and sleeping in the streets. I don’t see how a theme park could be good for families.”

Of course what many protesters feared was not just the park but the 21st century itself. Like it or not, modern-style capitalism will soon come barreling into Transylvania, and with it will come not only jobs, investments and opportunity, but also flash, tinsel and trash. There’s already a disco just a few steps from Sighisoara’s beautiful Clock Tower, and the basement of City Hall is home to a gaudy bar called Dracula’s Club, which is announced by a bright-yellow awning, a huge mock-up of a paper cup bearing a Coca-Cola logo, and a heavy rock beat. How long will it be before Sighisoara takes on the carny-town atmosphere of souvenir shops, cotton candy and tour buses? How soon before the local kids are gorging on vampireburgers and greasy French fries, or maybe cruising those quaint cobblestoned lanes for drugs?

Those were the kinds of anguished questions being asked not only in Sighisoara but worldwide, wherever aesthetes considered the matter. Last summer England’s Prince Charles, an architecture buff and ardent preservationist, added his own influential voice to the rising chorus of dissent when he declared that “the proposed Dracula Park is wholly out of sympathy with the area and will ultimately destroy its character.” Suddenly seized with doubt, tourism minister Dan hired a team of consultants from Pricewaterhouse Coopers to make a feasibility study and retreated uncharacteristically into a shell of silence.

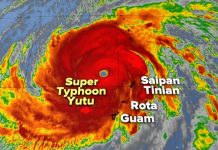

In November, Dan announced on national TV that Sighisoara would be spared after all, and he followed up in February by revealing that the town of Snagov, just north of the Bucharest airport, was now his choice as the park site. Romania’s intellectual and artistic community heaved a collective sigh of relief. The developers had lost; Transylvania had won. As for Dracula himself, it wouldn’t have surprised anyone very much if the mocking sound of his demonic laughter could be heard echoing once again throughout the alleyways of the medieval citadel that, for now at least, has escaped his curse.

GETTING THERE

The Romanian Tourist Office in New York offers comprehensive information at www.RomaniaTourism.com. Maps and print brochures such as “Transylvania-Cultural Centers” and “Dracula-History and Legend” are available from the Romanian Tourist Office, 14 East 38th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10016; by calling 212-545-8484; or by e-mail: rontoăerols.com. Mini guidebooks and advice from recent travelers to Romania are availableat www.lonelyplanet.com.

INSIDE TIPS: Visit Snagov soon, while there are still secluded picnic spots aplenty. The magnificent 16thcentury church where Vlad Tepes is supposedly buried is on a nearby island in Snagov Lake. To get there, ask locals where on the lakeshore to find “Ana.” For î1.30, she will take you to the island and back in her rowboat. Small pensions all around Romania are terrific bargains.

FOR THE GOURMET: If you’re up for the ghoulish, try the cornball-spooky Dracula Club in Bucharest. The butter in their chicken Kiev is colored deep red. Other restaurants offer various versions of “stake” dinners.

Rudy Chelminski